Why crypto tokens?

Understanding the role tokens play in crypto and an attempt to explain why tokens have value

I always viewed crypto/blockchain tokens as a way to fundraise and skirt securities laws — after all, it’s much easier to deploy a token contract on the blockchain and do some IDO than register with the SEC and go through the process of an IPO.

And plus, fundraising through tokens is cool, because a lot of the time, the general public (not just “accredited investors” like in TradFi) have access to these IDOs and other means of permissionless fundraising, which often means early users of the project (which is launching the token) have a chance to acquire a stake in it! This leads to better incentive alignment (as it’s pseudo user ownership) and hence potentially better price action for the token, but also means retail gets scammed more!

While I have come to refine my position on tokens, my core critique still remains: most tokens in crypto are just scams that allow insiders to profit at the expense of uninformed retail (and, no — the SEC’s existence won’t “mitigate” this) and exist because it’s the only way for insiders to profit — because they know they can’t profit from the product.

Now, I’d say bitcoin is the only case where the asset in some sense is the product, but for most tokens, this won’t be the case.

So, that begs the question: what are tokens actually good for? Are they actually useful in any way, shape, or form?

I’d argue that albeit my core critique laid out above is valid, used correctly, tokens can make or break a project, since most projects in crypto cannot flourish without tokens.

This boils down to the chicken or the egg problem, wherein you have two or more parties that are required for a product to function, but they all will only perform the desired actions if the others do — so in the end no one does.

It’s a classic coordination problem — but a problem that can be solved with tokens!

Let’s break this down.

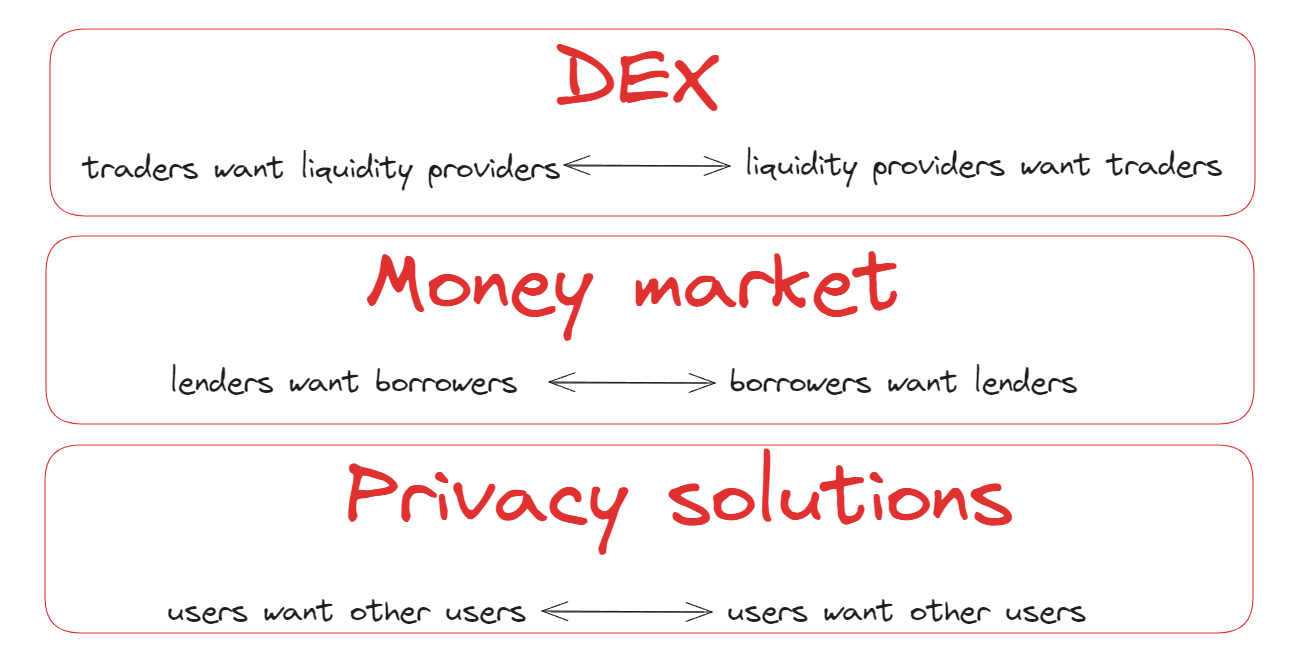

For most blockchain primitives such as DEXs (spot, perps, etc.), money markets like Aave, privacy solutions like Tornado Cash, they all need to build up some network effects to be useful, or in some extreme examples, even work — as seen in the image below, they need to get to the critical mass before accumulating networks effects and increasing the overall value of the network.

Tokens can help them get there!

Let me explain what I mean — as seen in the example below, there are some conditions projects need to fulfil before they’re useful or even work at all.

For DEXs, traders want liquidity providers before they place a trade, or else they’ll have unfavorable execution, but liquidity providers want traders to trade on the platform before they provide liquidity — I mean why would I provide liquidity to a platform on which no one is trading and hence paying no fees to me to provide liquidity?

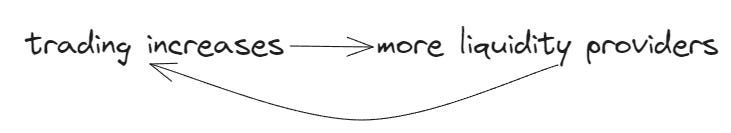

But once “enough” liquidity is on a platform, traders can start to trade there with favorable execution, generating more swap fees for liquidity providers, which acts as an incentive to provide liquidity — enacting a virtuous flywheel as seen below, wherein liquidity begets liquidity.

But there needs to be a “baseline” amount of liquidity for that to happen, and that’s where tokens can act as a sort of “bootstrapping/cold-start mechanism” (I write about this at length here) in the short run until the critical mass, in this case the baseline liquidity, is reached and the product, in this case the DEX, is self-sustaining.

To be more specific, tokens would be used to incentivize one side of the equation (in this case liquidity providers) to do the desired task from the perspective of the product (in this case, provide liquidity) so that the desired task from the other side/party (in this case, traders) is induced (trading in this case).

With DEXs, these incentives usually take the place of pool2 emissions, which you can read about here. Basically, liquidity providers just get the native token of the project in order for them to be financially incentivized to provide liquidity, and the hope is that in the long run, these emissions/incentives would no longer be required as traders pay fees to liquidity providers as they trade, obviating the need for these emissions/incentives.

A similar dynamic manifests itself with money markets, wherein lenders want borrowers and borrowers want lenders and a baseline amount of lending needs to be established for markets to arise, which is where these incentives come again to perhaps accumulate enough lending activity so as to sustain borrowing activity.

In some extreme examples, as I mentioned above, without other users of the product, the product is effectively useless.

With the examples of DEXs and money markets above, at least they work even in times of low liquidity, but in some cases like Tornado cash, if you don’t have enough usage of the product, it basically falls apart and becomes antithetical to the premise of the product — I won’t get into why this is, but it has to do with Tornado Cash’s design and anonymity sets, which you can read about here.

So in both cases above too, some amount of baseline adoption of the product is required for it to function well or even function at all, which is where tokens come in as a financial incentive.

Before moving on, I also want to contrast this approach with Web 2.0, since even in Web 2.0, a similar dynamic presents itself with the chicken and egg problem (applications such as Uber, Airbnb, etc., wherein riders and renters need drivers and landlords using the applications, respectively, while drivers and landlords would only be financially incentivized to contribute to the application where there is demand, which will only manifest, however, if they are already contributing to the platform). This is one of the reasons why in Web 2.0, it’s so much harder to scale your business in a vertical that requires established network effects to function (Uber, Airbnb, etc.), and legacy financial incentives such as rebates just fall short and eventually lead to failure for these businesses (now contrast this to crypto, where anyone can launch a token without needing to go through an arduous and extremely expensive IPO process and also distribute them through smart contracts using blockchain rails – these things are just unheard of in Web 2.0).

This “token incentive” approach sounds cool and all, but what actually gives these tokens “value” so as to be a financial incentive for these parties to come with their liquidity and sacrifice their next best alternative (opportunity cost) with their capital and time?

As a side note, I can’t stress enough that value is subjective — and everyone values things differently based on their circumstances, preferences, etc. and valuations are always done at the margin. So in lieu of my love for Austrian economics, when I say value I’m just generalizing it to someone wanting any amount of something for any price because of this abstract value.

After all, if these tokens were just something these parties sold upon receiving them, why would anyone put up their capital to receive something that’s objectively worthless?

This is where tokenomics design comes in.

We can design the economics of a token such that there’s an intersection between supply (these emissions/incentives used to bootstrap) and demand — basically, design these tokens so that tokens emitted/used as incentives are demanded by some party and are not useless (hence providing them this purported value).

Apart from mere speculation giving these tokens demand (which I will get to below), we can design tokens such they have demand stemming from, broadly speaking, value accrual and governance (the astute reader will remark that monetary premiums play a role here, but that’s a niche in crypto and only bitcoin and Ether are going after playing the roles of money).

Governance is an interesting thing, wherein governance itself can have value accrual (governance as value accrual was a narrative some time ago), in the instance of $veCRV (locked $CRV holding governance power) where $CRV gauge emissions are directed/controlled by governance, which came with value accrual as these emissions were demanded by protocols and DAOs looking to deepen their liquidity pools on Curve and hence placed bribes for governance to capture provided they vote for emissions to be directed to said pools, but even in instances like these, the underlying value being captured is the power over directing $CRV emissions — which in itself doesn’t give value to $CRV tokens.

So what gives $CRV tokens value?

Well, in the case of Curve Finance, half of the trading fees generated by the protocol and the interest paid (on debt) by users with open positions on Curve’s CDP protocol ($crvUSD) stream to $veCRV holders — so a claim on the cash flow generated by the protocol is, by the looks of it, what gives $CRV value, which then gives it further value as the $CRV emissions being controlled by governance in itself valuable to both accumulate bribes from protocols or DAOs or direct emissions to pools that said locker of $CRV is providing liquidity for (this will increase his yield but will only be economical when the potential bribe rewards are lower than the potential rewards if emissions are directed liquidity pools the locker is involved in — basically providing liquidity for).

Now, we can debate on what actually gives these $CRV tokens value — whether it’s this value accrual through revenue share, and by extension, governance as value accrual or just mere speculation — or both.

The way I see it, what gives tokens in general value is a claim on potential (or current if mechanisms like above are in place) future cash flow, but this cash flow is just a psyop (more on this below) and a cover for speculation being the biggest demand driver.

For instance, GMX, which has gotten a lot of attention lately for accruing “heaps” of value to token holders, only delivers around 2.81% real yield to token holders…

Not much, really — no one is buying into the token to get a 2.81% yield. The RFY (UST 10 yr) itself yields around 2x more — with much less counterparty and asset valuation risk (the underlying asset earning the yield in this case is $GMX — a highly volatile asset — at least relative to the U.S. dollar).

This is a testament to the fact that people don’t buy these tokens for yield, but rather as a way to speculate on the underlying product (Curve, GMX, etc.) growing to a fair valuation (investors believe what they’re investing in is undervalued and the price doesn’t reflect the “fair valuation,” or else why would they invest?) and accumulating more revenue for token holders, enticing more people to buy the token — remember, the biggest utility a token can have is its ability to be sold for someone else for a higher price than was used to buy it.

Revenue share in this case is a way to drive speculation!

It’s hard to pinpoint what gives rise to speculation and thus value, but I’d say psyops play a huge role — revenue share included.

In accordance with this logic, there’s a case study of Jade protocol, which was an OlympusDAO fork that had a “fair/intrinsic value,” i.e., like a sort of backing which was around one-fifth of the total market cap of their token. This was basically a psyop that distracted people from the fact that their token was inflating in the realm of 5 digits (remember the 10,000% APYs from the Olympus days?) per year, and the second they stopped advertising that and reminding people of that, the token’s price quickly went from $100 to below their $18 “backing” price (you can find the details in a good game theory series of articles here:https://medium.com/@game_theorizing/of-smoke-and-mirrors-part-2-the-godsfather-cd24ff7476da)! This might seem like a sort of tangential point, but I thought I’d bring it up to show what kind of an effect these psyops can have on the value of a token!

Apart from revenue share, there are a myriad of factors that can affect the value accrual for a token — with some examples like Curve through governance, or on blockchains like Ethereum where the fee (more specifically the base fee — priority fees can theoretically be paid in any token) paid needs to be in the native token, $ETH, and the cryptoeconomic security provided by validators on the beacon chain needs to be in $ETH, or in some other cases where you need to hold the token in order to be able to do something (access a gated community, use a product, etc.).

Now, as mentioned, governance in itself can be a form of direct value accrual, but in some cases is valuable indirectly (more on this below).

Lido’s governance token, $LDO serves as a relevant example — the $LDO token itself has no means (mechanisms) of direct value accrual — it has no revenue streams to it, and governing over the protocol doesn’t directly accrue any value to the token like in the case of Curve, but how come it has a market capitalization of $2.7 billion?

The real reason is the same as GMX — speculation on Lido accumulating more market share in the LST market and hence generating more revenue for the protocol (even if this doesn’t stream to the token holders)!

Growth stocks work in a very similar way, wherein future earnings are priced into today’s valuations regardless of whether they’re paid as dividends (revenue share or not).

In the case of Lido, it has an “advantage” (if you see it that way) over growth stocks, wherein through a democratic process, $LDO token holders (collectively becoming the “DAO”) can always vote to direct revenue back to token holders in case the market is “unfavorable” with respect to pricing Lido based on “fundamentals,” whereas as in growth stocks, holding the shares most of the time doesn’t entitle you to a vote over things like these, and this is usually confined to the board of directors.

This is what I mean when I say governance can be valuable indirectly.

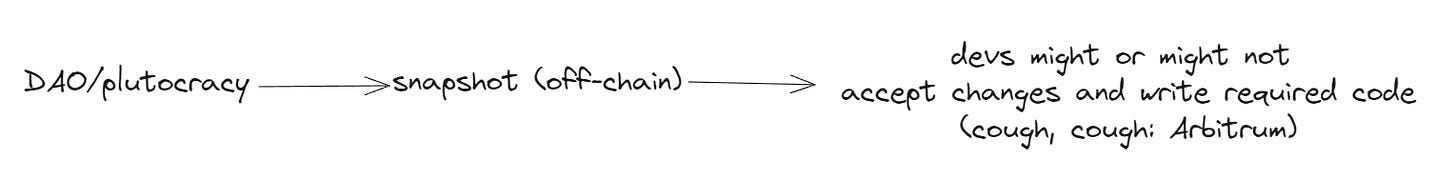

But DAO governance is usually a complete joke (I recommend reading Polynya’s 3 part series on Governance & DAOs — find them here, here, and here), and often a board of directors governing a project is more decentralized than a DAO doing so, as most governance architectures of DAOs look like this (I’ll write a detailed post on this soon to avoid making this post too long).

Not to mention these DAOs are just plutocracies and currently have very few ways of pivoting from that, as mechanisms like 1 person 1 vote cannot work on blockchains and in the digital realm in general (sybil attacks are too easy — in fact probably easier in Web 3.0 than in Web 2.0).

Plus, I’m more scared of governance being incompetent than centralized (cough, cough: Aave and basically most DAOs).

Furthermore, as I’ll elucidate in a future blog post, full-fledged DAOs from the outset do not work, are risky, and are very hard to achieve, and small increments in added decentralization don’t do anything (read this and this — the latter is a long and mostly tangential read from what I’m talking about but definitely worth a read).

At the project’s inception, making your product better should be the priority, not “decentralizing” your “DAO,” since (apart from my previous arguments) what’s the point of governing over a useless product?

Overall, there’s only so much “tokenomics design” can do, and it’s really not rocket science — build a good product that people actually use (a good acid test for this is if people use the product if there are no token incentives/no token incentives after critical mass is reached, as explained previously) and only use tokens to bootstrap network effects as explained above (which will require some value accrual). Perhaps also down the line using these tokens distributed to the community as a way of “decentralizing” the project.

Again — it’s not that hard if you keep it simple!

Until next time,

Imajinl

P.S.: catch me on Twitter/X here: https://twitter.com/imajinl and find my personal blog below if you want to read more of my writings!